コラム:パリジェンヌの東京映画レポート2 - 第7回

2010年8月20日更新

第7回:ゴダールの入門書「シャルロットとジュール」

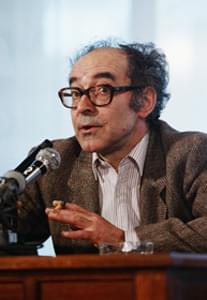

It is not easy to write about Jean-Luc Godard, as he has probably been the most complex and innovative figure of French cinema for more than 50 years now. As a leader of a group of filmmakers known as the “Nouvelle Vague” (the “French New Wave”) in the late fifties and a committed film director after 1968, he has had a strong influence on the cinema world during the 20th century, not only in France, but also in the whole world.

Copyright Aflo Co. Ltd. All rights reserved.

Whether you refer to his first movies in the 50’s、 to his romantic period in the 60’s (with movies starring Anna Karina, Brigitte Bardot, and Jean-Paul Belmondo), to the 70’s split between his political commitment (with movies signed by the Dziga Vertov group) and his co-productions with his companion Anne-Marie Mieville, to the 80’s and 90’s with a comeback to strictly speaking cinema movies, or to his earlier movies, Godard has always kept the same guiding principles: the cinema as an art to show the reality, of our world but also of the cinema itself. As Godard said himself: “"Pictures no longer bring anything new to the audience, because they have it 100 times a day on TV ... the only thing left is to show more truth about people’s lives […]”.

There are several elements that make Godard’s movies distinctive masterpieces, which are recognized as such in the whole world. First of all, Godard makes a constant use of what we call “mise en abyme”. Thus, the characters of his movies go to the movie theatre, shoot movies and talk about cinema. Following the guidelines of the New wave, shooting a movie is for Godard a means of showing things in a more realistic way and, more importantly, of proving what cinema is really about. In Detectives for instance, you can see a JVC camera which is filming and which suddenly turns to the real camera of the movie: a mise en abyme of two cameras.

A further element you cannot escape from when watching one of Godard’s movies is the detachment of the characters which always reminds us that we are watching a movie, that it is “only” cinema. We are torn between diving into the movie and its story, as we are used to, and observing how the movie is constructed. We are directly implicated and immersed in this fictional creation we know moviemaking is.

Thus, the actors often turn to the camera and it seems as if they were looking straight into the eyes of the spectator. There are countless examples of this detachment in Godard’s films. A woman is a woman for instance ends with Anna Karina winking to the camera, 2 or 3 things I know about her starts with a presentation of the actress, and not of the character she’s playing. And the characters even talk about the movie itself: in Joy of learning for instance, Léaud says “finally, this movie is a failure”.

All those elements may be quite surprising if you watch those movies nowadays, as we are used to movies that completely carry us away and make us dive into another world thanks to sophisticated special effects. It seems to be a completely different cinema universe…! But it’s kind of refreshing, even if it’s sometimes stunning to be confronted to actors and a scenario, rather than to characters and a story.

Godard's social and political preoccupations have often obscured his movies, but a lot of them are nevertheless deeply romantic and tackle a lot with the relationships between men and women. Those relationships are dominated by a permanent (often linguistic) incomprehension and the reconciliations are rare, sometimes even impossible because one of the lovers dies (in Breathless for example). Thus, in order to underline the fragility and ephemerality of the reconciliation in My life to live for instance, the moment is silent and undertitled. A quite original way of showing the reality, but at least it makes you think more deeply about which message the film director wants to convey.

Watching Godard movies makes you think about the origins of cinema. And it makes you also realize that there are finally no real limits to film making. A Godard movie can invigorate your interest for movies. And it definitely shows you that cinema is not called the seventh art for nothing!

[抄訳]

50年以上も革命児としてフランス映画界に君臨するジャン=リュック・ゴダール。彼について書くことは簡単ではありません。1950年代後半に始まった映画運動ヌーベルバーグ(フランス語で「新しい波の意」)の旗手として知られるゴダールは、フランス国内にとどまらず、世界中の映画作家たちに多大な影響を与えてきました。

1950年代に映画製作を始めたゴダールは、60年代にアンナ・カリーナ、ブリジット・バルドー、ジャン=ポール・ベルモンドら名優と組んで、数多くの傑作を残しました。70年代には政治的観念の違いから当時のパートナー、アンヌ=マリー・ミエビルとともに新進気鋭の映像製作グループ「ジガ・ヴェルトフ集団」を去るものの、自身の原点に立ち戻った80~90年代には精力的な製作活動を再開します。しかし、いつの時代にもゴダール作品に共通するテーマがありました。それは、“芸術としての映画が現実社会を映し出す”ということです。ゴダール自身、「映画はこれ以上、観客に新しいものを提供することはできないだろう。なぜなら、彼らはテレビで1日に100回は新しいものを目にするのだから。だから映画に残された道は、我々の人生についてもっと真実を語っていくことしかない」と言っています。

ゴダールの映画が独特とされるのは、幾つか理由があります。ゴダール作品では“紋中紋”(フランス語で無限の中に入るの意。一般的には向かい合った2枚の鏡の間に立って鏡を見ると、見た者のイメージが無限に複製されるという視覚体験のこと)という表現方法が多用されています。例えば、彼の映画の主人公たちは映画館に行ったり、映画を撮ったり、映画について議論したりします。また、「ゴダールの探偵」(85)では主人公が撮影しているJVC製カメラの映像と、その主人公を映すメインのカメラが混在し、まさにゴダール特有の“紋中紋”(無限の中に入ることの意)を体験できます。

ゴダールの映画を見ていると、観客は映画の世界観に浸りつつも、常に“映画を見ている”という事実から逃れることができません。それはしばしば役者がカメラを振り返り、観客を真っ直ぐに見つめているような錯覚を起こすからです。「女は女である」(61)ではアンナ・カリーナがカメラにウィンクして幕を閉じるし、「彼女について私が知っている二、三の事柄」(70)では冒頭に役者が映画についてのプレゼンテーションをするし、「たのしい知識」(68)にいたっては主人公が「最後に、この映画は失敗作だ」と宣言してしまいます。

ゴダールの政治的観念が作品に影を落とすことはあっても、基本的には男女のロマンスが描かれた作品が多いです。しかし、和解や仲直りといった関係性が描かれることはまれで、主人公が最後に死んでしまう「勝手にしやがれ」(60)のように、不変的な無理解や不仲について描かれた作品がほとんどです。今秋、マノエル・デ・オリベイラ監督の「ブロンド少女は過激に美しく」と併映される短編「シャルロットとジュール」(58)でも、ジャン青年はアパートを訪ねてきた元彼女シャルロットに14分間彼女の愚痴を言い続け、シャルロットは黙ってそれを聞くだけ。そしてシャルロットが最後に一言「私は歯ブラシを取りにきただけよ」と残し、ジャンのもとを去っていきます。これはゴダールならではの現実描写といえるでしょう。

ゴダールの作品を見ることは、映画の起源を考えるきっかけになります。そして、映画製作の無限の可能性を感じさせてくれるでしょう。ゴダール作品はあなたの映画への興味をかきたて、もはや映画を第7芸術だなんて言わせないことでしょう!